korean beauty guides

Hanbang and Traditional Korean Skincare

Hanbang skincare is a particular branch of Korean skincare that involves the use of herbal prescriptions and formulation techniques based on original principles of Traditional Korean Medicine (TKM) with incorporation of modern science.

This article wants to be a comprehensive introduction to the characteristics of Hanbang skincare and the principles behind it.

Disclaimer: I have personally translated the information and details in this article from original Korean sources, so I kindly ask you to credit my work if you intend to utilise any of the information provided in this guide.

Part 1: Hanbang Skincare

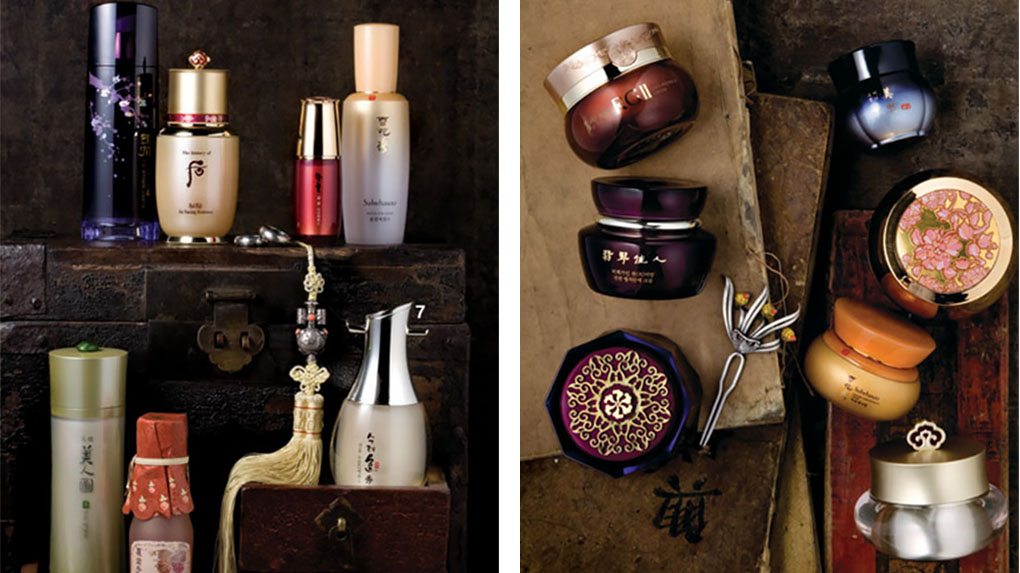

The History of Whoo

1.1 Characteristics of Hanbang cosmetics

The official guidelines for labeling and advertising of Hanbang cosmetic products provided by the Korean government, define Hanbang cosmetics as:

“Cosmetics formulated following herbal prescriptions described in the existing Korean Pharmacopoeia (KP), Korean Herbal Pharmacopeia (KHP) and in the Provisional Rule of Existing Herbal Medicines, or cosmetics formulated using herbal medicines above a certain standard1.”

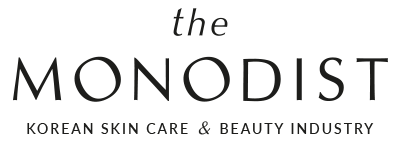

While standard cosmetics are designed to treat specific skin concerns over a short period of time, the primary goal of Hanbang cosmetics is to boost skin’s self-resilience and enhance skin’s self-recovery power using the principles of Traditional Korean Medicine (TKM).

In Traditional Korean Medicine, pathological conditions and health concerns are considered consequences of weakened body’s immunity. For instance, when a healthy body is exposed to the flu virus, its immune system will be strong enough to prevent the body from getting sick. On the other hand, a weak immune system is more vulnerable to disease and infection.

[source: The Chosun Ilbo]

Likewise, Traditional Korean Medicine sees skin concerns as signs of a physiological disharmony of the body. The primary goal of Hanbang skincare, which is based on the principles of TKM, is not treating specific skin concerns, rather harmonise the body to strengthen its immune defenses. In particular, Hanbang skincare has two main functions:

Unlike standard cosmetics, Hanbang skincare products are not classified by skin type. Rather, they aim to provide holistic care based on patterns of imbalances identified through TKM principles. Since Hanbang cosmetics mainly work on skin resilience, their main application lies in anti-aging skincare. In particular, the anti-aging lines of Hanbang skincare brands are based on the theory of aging and life cycles explained later in this article. Anecdotally, Hanbang skincare lines for very mature skin tend to be oilier than the ones for young skin so oily/combination skin types should keep that in mind.

1.2 Differences between Hanbang and standard cosmetics

[source: Harper Bazaar Korea]

1.3 Korean cosmetic regulations on Hanbang cosmetics

Despite being inspired by the principles and therapeutic prescriptions of Traditional Korean Medicine, from a legal standpoint Hanbang cosmetics are not considered any different from general cosmetics in Korea.

In 2012 the Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety issued guidelines for labeling and advertising of Hanbang cosmetic products1. The guidelines give a definition of Hanbang cosmetics and stipulate that, in order for a cosmetic to be marketed as “Hanbang”, it should contain at least 1% of Hanbang herbs (1g for every 100g/100ml) and it should comply with the safety standards set by the “Standards and Test Methods for Residues and Pollutants in Herbal Medicines”.

1.4 Chinese labelling regulations of Korean Hanbang cosmetics

On 14 December 2018, the Shanghai FDA (SHFDA) banned the use of the word “Hanbang”, either in Korean (한방) or Chinese language (韩方), on the packaging of Korean cosmetic products sold in China. The ban was later extended to the rest of the country. The Chinese health authorities argued that the word “Hanbang” could lead consumers to mistake these cosmetics for drugs, since the word ‘bang’ (in Korean “방”, in Chinese “方”) translates to “medicine” in Chinese 4.

Following this decision, and considering China is the main foreign market for these products, many Korean beauty brands decided to remove any reference to “Hanbang” from the packaging of their products.

1.5 Efficacy of Hanbang cosmetics

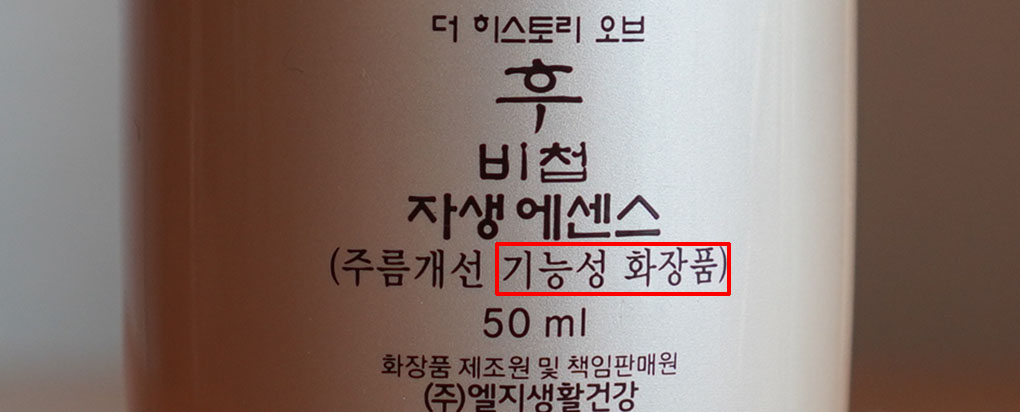

Some Hanbang cosmetics with particular functions are recognised and regulated as “functional cosmetics” (기능성화장품). Article 2 of the Korean Cosmetics Act5 defines “functional cosmetics” as products that aid in functionally improving or changing the condition of skin or hair. As of 2021, the Korean law identifies 11 categories of functional cosmetics6:

Marketing claims related to functional cosmetics (i.e. whitening, anti-wrinkle) are strictly regulated and subject to a complex system of evaluation and pre-market approval by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). Brands that want to use regulated functional claims to promote their products, must submit to the MFDS documentation that shows the safety and clinical effectiveness of the products before market release. The clinical effectiveness must be evaluated by independent testing agencies appointed by the government, which operate by following standards based on modern science.

Approval process of functional cosmetics in Korea

In accordance with Korean cosmetic labeling requirements, when a cosmetic product is approved as a functional cosmetic, the words “기능성화장품” (“functional cosmetics”) must be displayed on the packaging, and the information should also be included in online product pages7. This allows consumers to identify products that were legally approved to have functional effects.

1.6 Hanbang skincare product terminology

The names of Hanbang skincare products frequently incorporate traditional terminology rooted in the principles of Traditional Korean Medicine, which may lack direct translations in English. Below is a list of the most common terminology used in Hanbang skincare and their correspondent English translations.

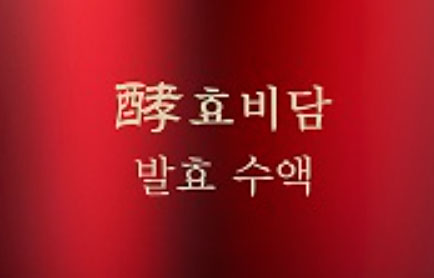

수액 (养水) = /soo-ek/

Literally “Nourishing Water”. Usually translated as “Balancer”, “Softener” or “Toner”. i.e. the original name of Sooryehan’s Hyobidam Fermented Toner is “Hyobidam Balhyo Soo Ek” (효비담 발효 수액) .

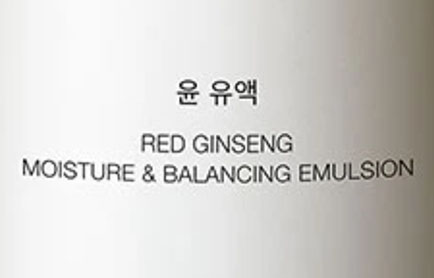

유액 (养乳) = /yoo-ek/

Literally “Nourishing Milk”. Usually translated as “Emulsion” or “Lotion”. i.e. the original name of Donginbi’s Red Ginseng Moisture & Balancing Emulsion is “Yoon Yoo Ek” (윤 유액).

진액 (精华) = /jin-ek/

Literally “Concentrated Fluid”/ “Essence” . Usually translated as “Essence”, Serum” or “Concentrate”. i.e. the original name of Yehwadam’s Hwansaenggo Ultimate Rejuvenating Serum is “Hwansaengoo Boyoon Jin Ek” (환생고 보윤 진액).

1.7 Popularity of Hanbang skincare

Sulwhasoo (1997)

Although historical documents show that the topical use of medicinal herbs in Korea can be traced back to the Goryeo dynasty (918), the application of Traditional Korean Medicine principles to mass-produced skincare products is a fairly recent phenomenon.

The first Hanbang skincare brand in the history of Korean beauty dates back to 1973, when the Amorepacific Group (then called “Pacific Group”, 태평양) launched “Ginseng SAMMI” (진생삼미) a beauty brand formulated using ginseng saponin ingredients8.

The brand was exported to 34 countries and recorded 20 million dollars in sales, drawing more attention abroad than in Korea where ginseng was perceived as an expensive herb9.

In 1980 Jung San Biotechnology (정산생명공학), a company of herbal health supplements tried to replicate this success with the launch of a beauty brand called “Baekoksaeng” (백옥생)8 , but it wasn’t until 1997 that Hanbang skincare gained recognition with the Korean general public.

In 1997 Amorepacific relaunched their iconic Hanbang brand under the name “Sulwhasoo“, with new products developed based on their extensive research of Traditional Korean Medicine prescriptions and skin aging. The new brand became an instant success with Korean consumers, surpassing 134 million dollars in sales within the first three years8.

This, along with the great popularity of historical television series centered around Korean medicine like “Dae Jang Geum”, inspired many other companies like LG Household & Health Care, Coreana Cosmetics and Missha to launch Hanbang beauty brands in the early 2000s8.

Missha (2015)

By 2006 the domestic Hanbang skincare market was estimated to be worth 780 billion Korean won (around USD 655 million), with a growth rate of over 10% per year10.

Nowadays, Hanbang skincare is mostly popular among 30+ Korean consumers11 and Chinese consumers of all ages. In particular, the Chinese market for Korean Hanbang cosmetics was valued at 3.4 trillion Korean won (around USD 3 billion) in 201912 with names like LG’s “The History of Whoo” outperforming brands like Shiseido and La Mer13.

1.8 Beauty companies with research centres dedicated to Hanbang

1.9 Hanbang beauty brands (by parent company)

SHINSEGAE GROUP

Yunjac (연작)

Available at:

Jolse

W.Concept USA

Stylekorean

EATH LIBRARY

Eath Library (이스라이브러리)

Available at:

Musinsa Global

LOSHIAN

Shihyo (시효)

Available at:

MEDICAL O

Hanisul (하니술)

Available at:

Hanisul US

Part 2: The Basics of Traditional Korean Medicine

Traditional Korean Medicine (TKM) is a form of oriental medicine based on medical practices originated in Korea. Like all branches of Oriental Medicine, TKM shares the same theoretical background with Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), but in time Chinese medicine was adapted to the Korean environment and culture and Korean Medicine became a distinctive regional tradition, with medical theories and therapies that are unique to Korea.

Similarly to TCM, Traditional Korean Medicine is a holistic medical practice that views the human body as a balanced network of interconnected systems, rather than as a collection of organs to be treated individually. When this balance is broken, the whole system is affected and illness arises. These imbalances are commonly attributed to external, internal or lifestyle factors and the goal of TKM is to preserve or restore the body’s natural equilibrium.

The theoretical framework of Oriental Medicine is based on philosophical beliefs originating from the observation of natural phenomena and the way individuals reflect and are affected by natural processes. A good example is the concept of Yin and Yang: Oriental Medicine observes that everything in nature is made of two opposite elements (i.e. dark/light, cold/heat etc) so humans, which are part of the natural world, are also believed to reflect this duality in their bodies.

Since these abstract concepts cannot be proven using methods accepted by modern science, Oriental Medicine is commonly classified as a form of complimentary and alternative medicine (CAM).

Although the mechanism of action of TKM therapies is not clearly understood from a modern scientific perspective, we do know that some of these therapies produce clinically observable results. Perhaps the most notable example is the 2015 Nobel-Prize-winning research on Artemisinin and its application in malaria treatment.

Tu Youyou receives the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (source: Nobel Prize)

In Korea, Traditional Korean Medicine is considered a valid healthcare system. Studies reveal that modern medicine is overall used the most, especially for complex and serious health conditions, but some categories of chronic diseases are more commonly treated using TKM therapies16.

Since the approval of the National Medical Act in 1951, South Korea recognises Korean medicine as legally equivalent to Western medicine, in what is commonly referred to as “a dual healthcare system”. In Korea therapies based on Traditional Medicine are covered by national health insurance and TKM medicines can be easily purchased from regular pharmacies.

Korean herbal medicine prescriptions are regulated and standardised as part of the Korean “Pharmaceutical Affairs Act”, the “Korean Pharmacopoeia” (KP), the “Korean Herbal Pharmacopoeia” (KHP) and their related enforcement rules, and the profession of Korean Medicine practitioner is regulated by the “Medical Service Act”. While there are still many challenges before TKM becomes internationally recognised an evidence-based science, the industry is certainly not as unregulated as some Western media outlets suggest and South Korea is making significant efforts to standardise and regulate the practice.

Furthermore, Korean national institutions are actively promoting the integration of modern healthcare and traditional medicine through bills like the 2013 “Oriental Medicine Promotion Act”, an act meant to support the standardisation and advancement of TKM practices by modern scientific standards through financial support of research and specialised institutions17.

A particularly meaningful initiative is the foundation of the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, a government-funded research institute with the goal of researching and standardising Oriental Medicine therapies using modern scientific standards and technology. The institute is also responsible for publishing “Integrative Medicine Research“, a quarterly, single-blind peer-reviewed, open access journal focused on evidence-based scientific research in integrative medicine, traditional medicine, and complementary and alternative medicine18.

2.1 Main medical therapies

Herbal prescriptions

Herbal remedies made using plant-derived, mineral or animal-derived ingredients and following formulation principles of TKM. The remedies can be both for internal and external use.

Acupunture

Therapy that involves the stimulation of particular energy points through the insertion of needles on the body.

2.2 Key principles of Traditional Korean Medicine

QI:

In Oriental Medicine, Qi represents the intangible vital energy that runs through all living things, including the human body. In the body, it’s believed that Qi is essential to maintain a person’s health. It’s the vital force that powers the physiological functions of all organs and protects the body from external pathogens.

Diseases and health conditions are interpreted to be the result of Qi imbalances (i.e. stagnation, deficiency etc).

Note that in Traditional Chinese Medicine this word is also romanised as “Qi”, but pronounced “Chee” (氣), while in Traditional Korean Medicine it’s romanised and pronounced “Qi” (“기”).

Yin / Yang:

Yin and Yang is a philosophical concept used to describe the duality of natural phenomena. Just like light and darkness, hot and cold, happiness and sadness etc. everything in the universe exists as two opposing interdependent forces called “Yin” and “Yang”.

In Oriental Medicine, the parts and functions of the human body are also classified into “Yin” and “Yang” and health is defined as the dynamic equilibrium between these forces. Illness arises when this balance is disrupted, and TKM therapies aim to preserve or restore this delicate harmony.

The two main substances of the human body are also described in terms of Yin and Yang: Qi is Yang in nature (dynamic and transforming), while Blood (which is not to be interpreted in the Western anatomical sense) is described as a denser form of Qi and is Yin in nature (fluid and substantial). Since they have a Yin and Yang relationship, Qi and Blood are mutually dependent. Qi produces and circulates Blood throughout the body, while Blood nurtures and maintains the Qi. This relationship is described in classic literature as “Qi is the commander of Blood and Blood is the mother of Qi“.

Meridians:

In Oriental Medicine, meridians (in Korean 경락, “Kyeong-rak”) are considered the pathways through which the vital energy Qi flows and is distributed across the body. Disturbances and blockages in these channels are believed to lead to Qi stagnation and disease.

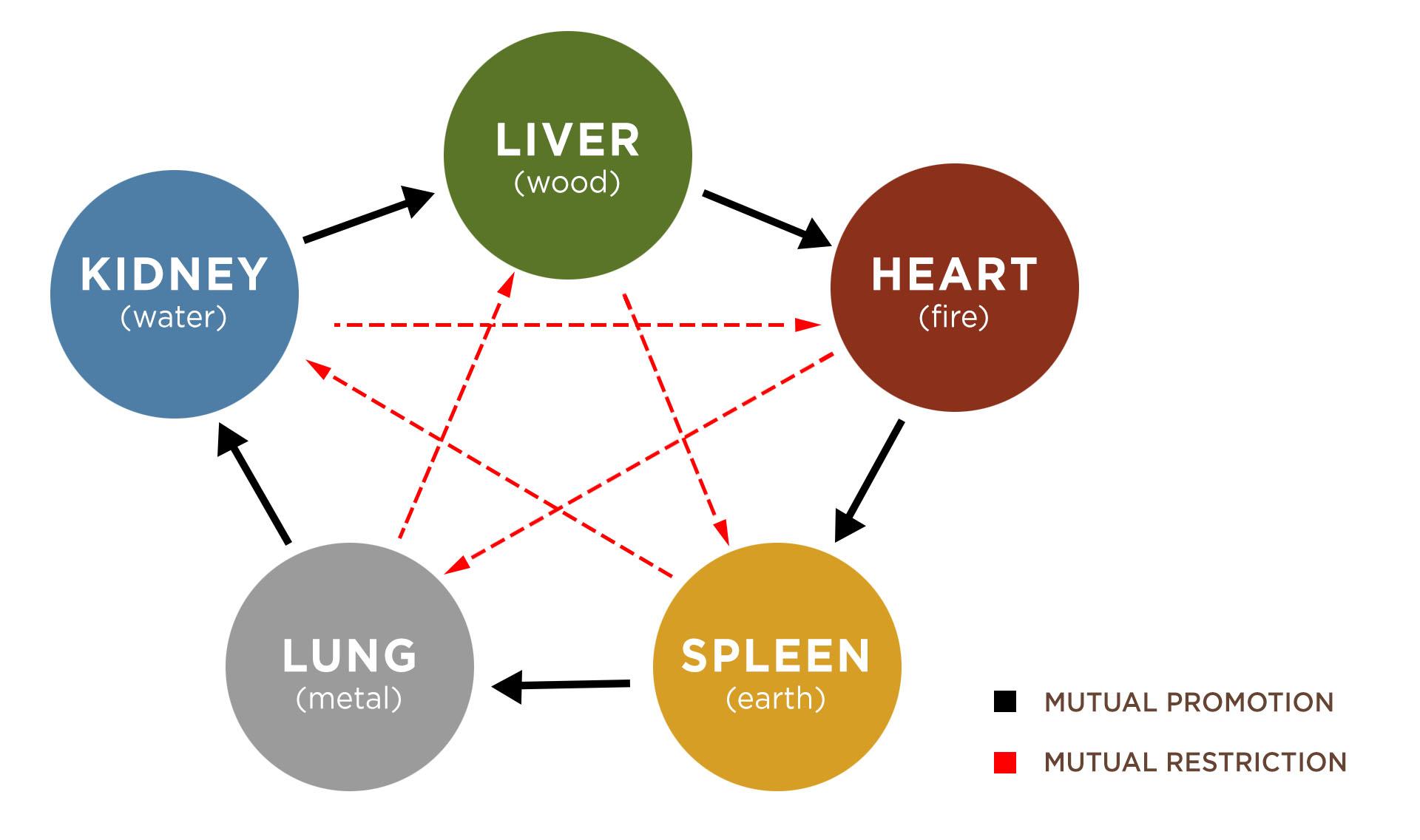

The Five Phases / Elements:

The Five Phases is the philosophical notion that all changes in the universe happen in a pattern of five stages. The five stages correspond to five natural elements:

As part of nature, the internal organs of the human body are also believed to correlate with the Five Phases according to their behavior and function in the body.

There are two cycles of transformation that keep the five phases in equilibrium.

These interactions are used in TKM to understand the cause of a disease and its treatment. i.e. if there is excess qi in the liver (liver qi stagnation), the spleen will be weakened since Wood (Liver) suppresses Earth (spleen), so an effective therapy would be to abate Wood (Liver) and support Earth (spleen) with remedies that have those properties (refer to the chapter “herb properties”).

The Five Elements Principle is referred to as “O Haeng” (오행) in Korean, and Wu Xing (五行) in Chinese. This principle and the colours associated with it are the inspiration behind “Obangsaek“, a palette of traditional colours that are ubiquitous in Korean culture25.

2.3 Aging in Oriental Medicine: the cycle theory

In Oriental Medicine, the aging process is considered the consequence of the progressive depletion of Jeong (essence). Note that, while in Korean essence is referred to as “Jeong” (정), in Chinese it’s called “Jing” (精).

According to this theory, each person has both a congenital essence (a fixed amount inheritated at birth from their parents) and an acquired essence obtained from food and drinks. Both types of essence are stored in the Kidney and they provide the energetic basis for growth, development and all living activities. It’s important to stress out that there is no correspondence between TKM organs and Western anatomy, so in this context Kidney is not to be intended in the anatomical sense.

When a person grows old, they gradually consume all their available essence until exhaustion, which coincides with death. Jeong (essence) and Qi (vital energy) have an interdependent yin/yang relationship: Jeong is the material basis of existence that is constantly transformed to release Qi, while Qi transforms food to nourish Jeong.

In particular, it’s believed that this depletion of Jeong (an in turn, Qi) develops following predictable periodical cycles (“life cycles”), where each cycle is defined by specific physiological changes and patterns.

The characteristics of each life cycle are described in the first chapter of the Hwangjenaegyeongsomun (in English “The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine“), a Chinese medical text considered the foundation of Oriental Medicine.

In women:

There are 7 stages of a woman’s life, with each cycle changing at an interval of 7 years.

In men:

There are 8 stages of a man’s life, with each cycle changing at an interval of 8 years.

2.4 Classic texts of Korean Medicine

The “Regulation on Approval and Notification of Herbal (crude) Medicinal Preparations” (one of the Enforcement Rules of the Korean Pharmaceutical Affairs Act) recognises the validity of herbal medicinal preparations based on recipes found in 10 historical textbooks of Traditional Korean Medicine19. Herbal prescriptions that are not based on existing recipes found in these books, are subject to pre-market evaluation of clinical efficacy following modern scientific standards.

The books are:

Part 3: Hanbang Herbal Remedies and How They’re Formulated

[source: Cosmax]

In this section I’m going to analyse the defining characteristics of Hanbang herbs and the principles used to combine them to form Hanbang prescriptions (oral or topical).

3.1 Hanbang herbs

The Korean medicine codex, which consists of the Korean Pharmacopoeia (KP) and the Korean Herbal Pharmacopoeia (KHP), currently recognises 601 crude herbal substances24. The herbs are either:

The active principles and therapeutic effectiveness of herbal substances depends on a variety of factors, most notably: species, growing environment (quality of the soil, quality of water, climate, hours of sunshine etc), harvesting conditions (wild harvesting, natural foresting, cultivation, time of harvesting etc) and processing methods.

A prime example is Panax Ginseng, one of the most expensive Hanbang herbs. Not only wild ginseng and cultivated ginseng present significant morphological differences, but wild ginseng was also shown to contain at least 10 times the amount of active compounds of cultivated ginseng20. The different market price of the two varieties reflects their different effectiveness.

Different morphological characteristics of Wild Ginseng (sx) and Cultivated Ginseng (dx). (source: YTN)

In Oriental Medicine, “Daodi” is a term that indicates medicinal herbs with the highest pharmacological properties, grown in specific geographical areas with specific natural conditions and being harvested and processed following specific standards. In 2015 the Korean Institute of Oriental Medicine published a guide on Korean medicinal herbs, their varities, characteristics and original growing environment. The guide is available for free on the KIOM’s website (in Korean language).

3.2 Herb properties

Hanbang prescriptions usually consist of a complex combination of multiple herbs. The herbs used in the prescriptions are not meant to treat symptoms of diseases, like in Western herbology, but they’re selected to target precise patterns of disharmony in the body.

i.e. in the case of excessive sweating, the Western herbology approach is to directly target the main symptoms of the condition by using natural remedies like green tea that help constrict sweat glands. The Hanbang approach on the other hand, looks at the patterns associated with sweating (mainly: excessive body heat and leakage of fluid) and prescribes herbs to treat these patterns, even if they’re not directly linked to overactive sweat glands.

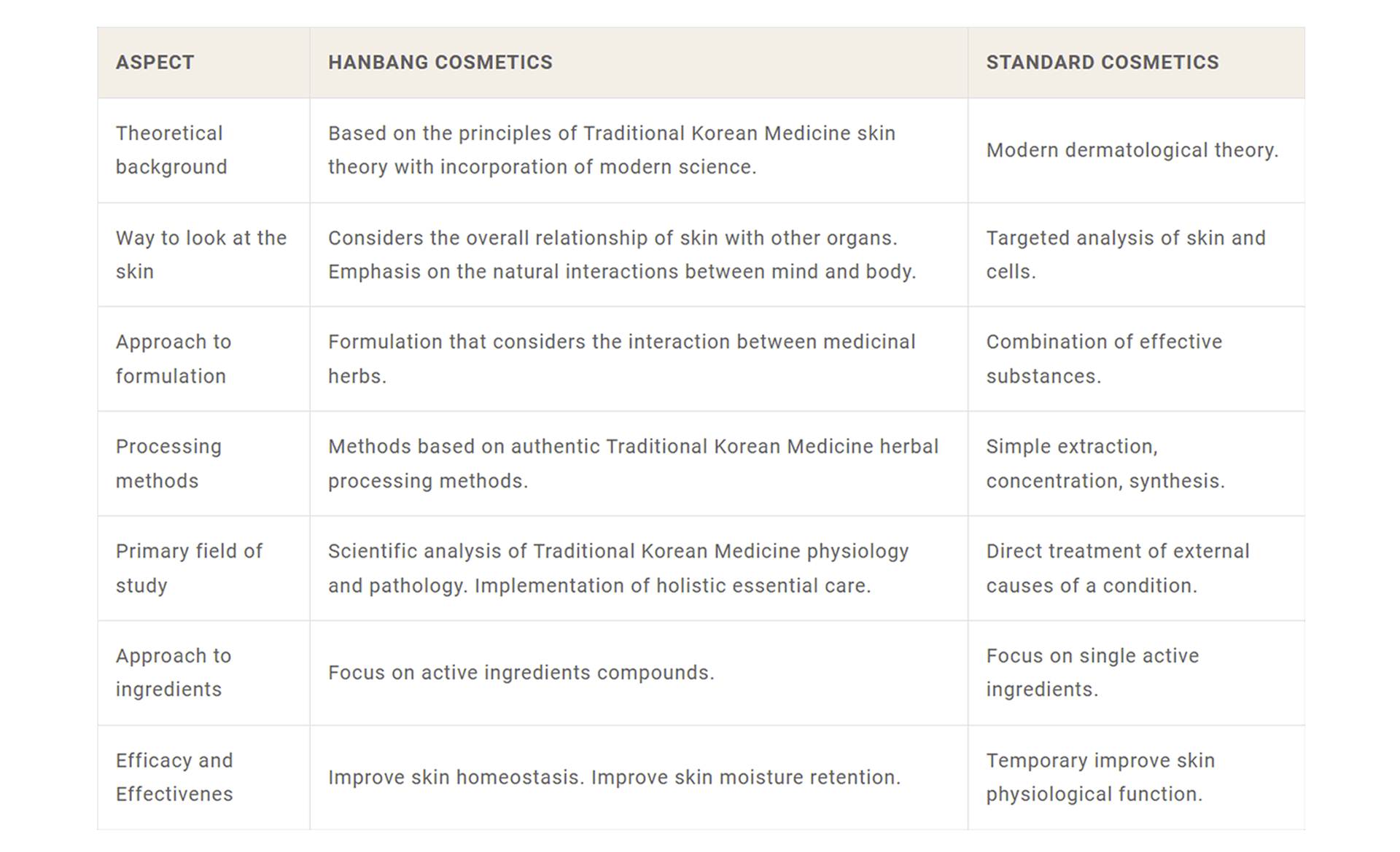

Each herb has a different nature and understanding the natural properties of herbs can help us understand what types of patterns each herb can treat.

Temperature:

The temperature of a herb is determined by observing the herb’s effect on the body (i.e. mint is considered a herb with a cool nature). Herbs are classified into:

Herbs with hot/warm properties can be used to treat conditions considered cool or cold in nature, and viceversa. Neutral herbs can be used to treat both cold and hot conditions. Treating hot with hot and cold with cold is strongly discouraged.

Additional properties:

Direction:

Lastly, some herbs have directional qualities that show the inclination and direction of their action. These properties are used to guide the therapeutic effect of the other herbs to a particular area in the body or counteract pathological actions that are moving in the opposite direction.

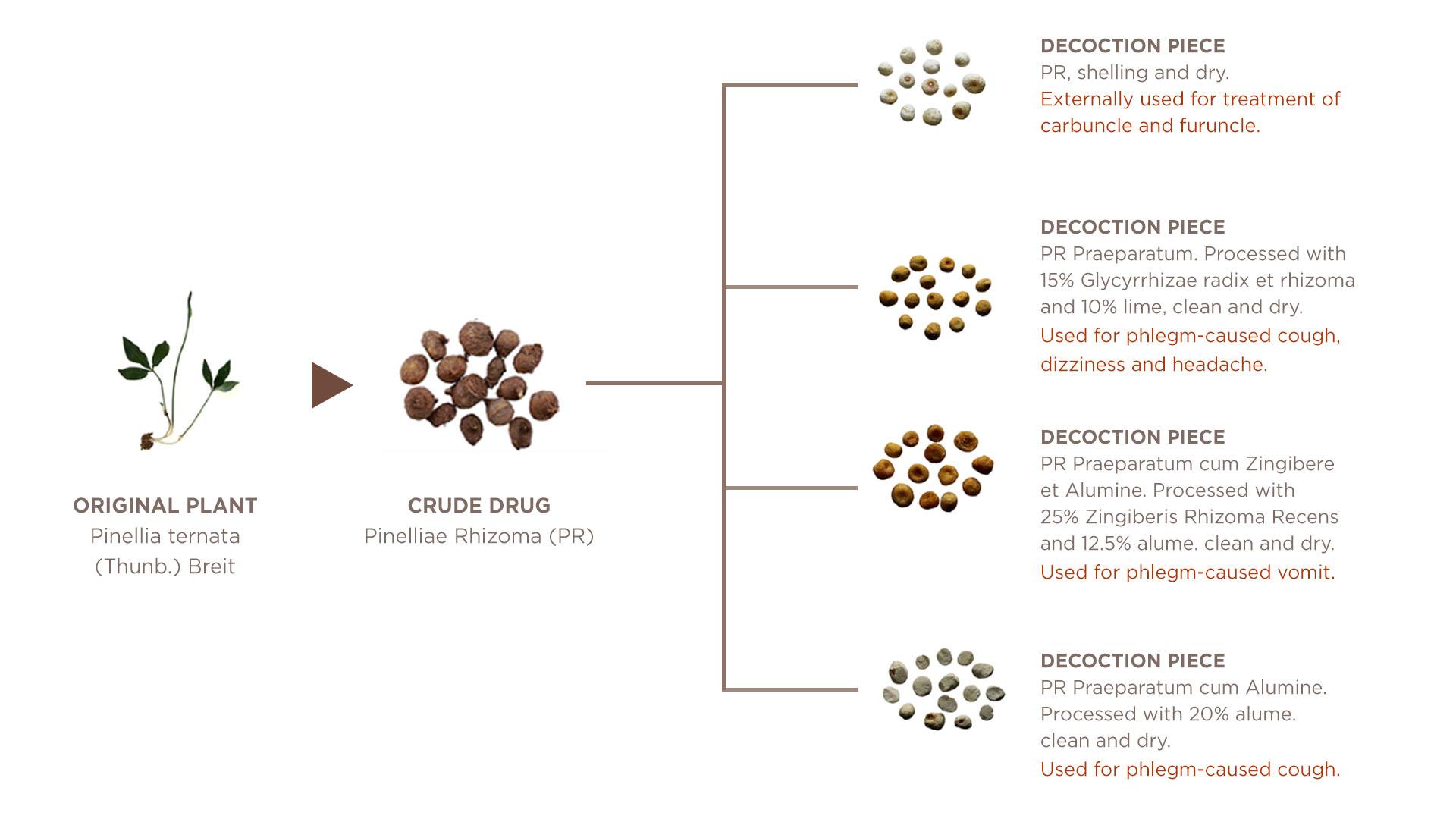

3.3 Herb preparation and processing methods

Along with the quality of raw materials, the effectiveness of Hanbang prescriptions depends on how the herbs used in these formulas are processed and extracted. In Oriental Medicine, processing methods are applied to raw herbal materials to accentuate or diminish particular properties of that herb for a specific therapeutic use. The correct preparation of its herbal components, insures the optimal effect of the final formula.

Traditional herbal processing methods are known as “Po Jae” (포제) in Korean and “Pao Zhi” (炮制) in Chinese, and they represent an integral aspect of Traditional Korean Medicine. The main objectives of the processing methods are:

How different processing methods can affect the properties and uses of an herb. An example of the significance of processing methods comes again from Panax Ginseng.

“Triterpene saponins were found to be the main bioactive constituents of Ginseng, which has anti-oxidant, anti-diabetic, immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities. After processing by steaming and drying, the chemical profiles are remarkably different between processed and non-processed Ginseng. The structural transformation of ginsenosides in processed Ginseng, which proved to have more potent bioactivities, contributes to its enhanced efficacy21“.

There are many methods to process herbs before usage, with each option having distinctive effects on the benefits and usage of a certain herb. The choice of a particular processing method over another, as well as the specifications of the process (i.e. how long a material should be steamed), depend on the characteristics of the original material and the desired therapeutic effect.

Some of the most common processing methods used in Traditional Korean Medicine are outlined below.

Basic preparation

Methods include: washing, pulverisation, slicing, cutting or defatting.

Processing herbs with the aid of water

Materials are treated with the aid of water or other liquids to eliminate impurities and refine the characteristics of the remedies. Methods include: rinsing and washing, moistening, soaking or aqueous trituration.

Processing herbs with the aid of fire

Materials are exposed directly or indirectly to fire until they become yellow, brown, carbonized or calcined. Methods include: stir-frying without excipients (dry-frying), stir-frying with excipients (solid or liquid), calcination, roasting, baking or blast-frying.

Processing herbs with the aid of water and fire

Materials are processed with the intervention of heat and certain liquids. Methods include: steaming, boiling, scalding, dip calcining or distilling.

Fermentation and Germination

Materials are exposed to a certain humidity and a certain temperature until they ferment or germinate.

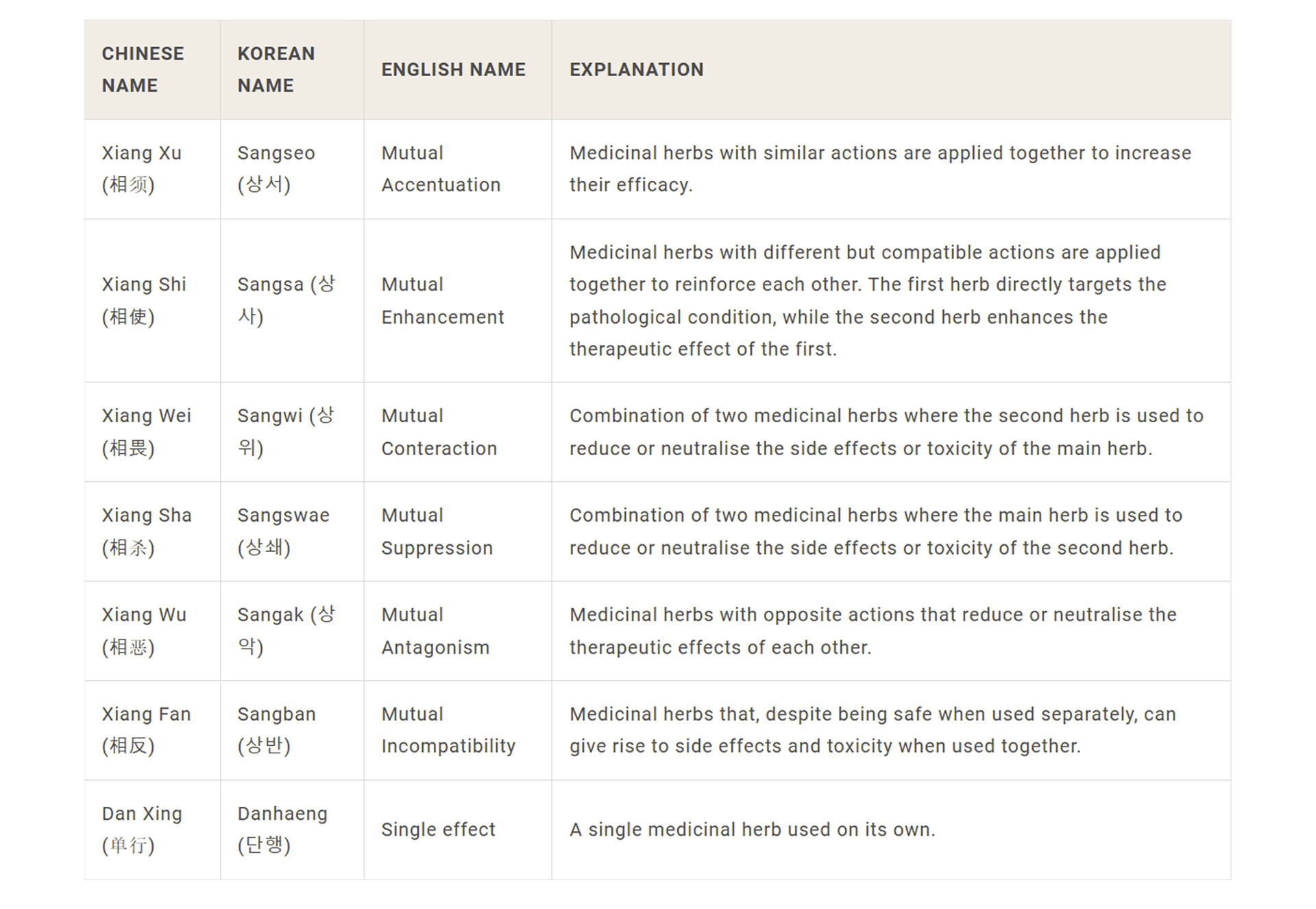

3.4 Herbal compatibility and interactions

The use of individual herbs in Hanbang herbal prescriptions is rare, as they usually consist of a synergistic combination of multiple substances. These prescriptions are formulated in accordance with the principles of the “seven-relation compatibility”, a theory used to determine whether or not various herbs are compatible with each other and how they interact with each other.

[click to enlarge]

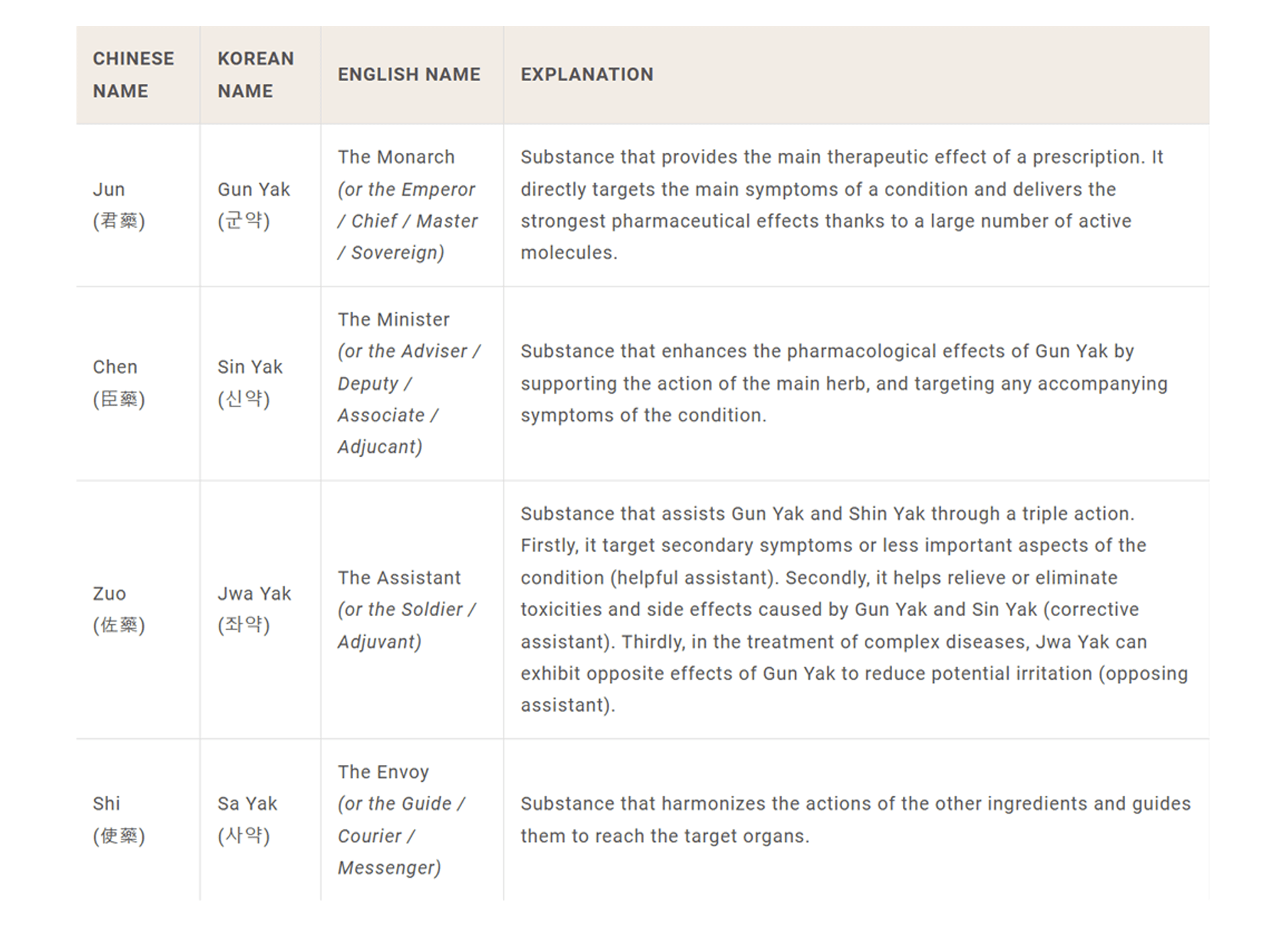

3.5 Combining medicinal substances: the Gunsinjwasa (Jun-Chen-Zuo-Shi) principle

As mentioned, Hanbang prescriptions usually consist of a complex combination of multiple substances with different medicinal properties that work synergistically to provide treatment for a certain condition.

The synergistic interactions among the ingredients of a prescription are believed to boost the bioavailability of active components in the formula22. The concept of synergy is a key part of Oriental Medicine and it’s different from the concept of simple addition. In fact, synergy occurs when the combination of multiple components produces a total effect that is greater than the sum of its individual elements.

These synergistic formulas are constructed following the principle of “Gunsinjwasa” (“군신좌사”, from the Chinese “Jun-Chen-Zuo-Shi”, “君臣佐使”), a complex hierarchy of actions and functions designed to target all aspects of a condition.

[click to enlarge]

Some simple prescriptions can contain only the main principles (Gun Yak and Sin Yak) or a substance can serve more than one function within the same formula.

A 2015 study by a Korean research team led by Professor Lee Sang Yup from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at KAIST, found that not only prescriptions formulated following the Gunsinjwasa principle had a synergistic mechanism, but they also shared significant structural similarities to human metabolites, especially when compared to Western medicinal prescriptions23.

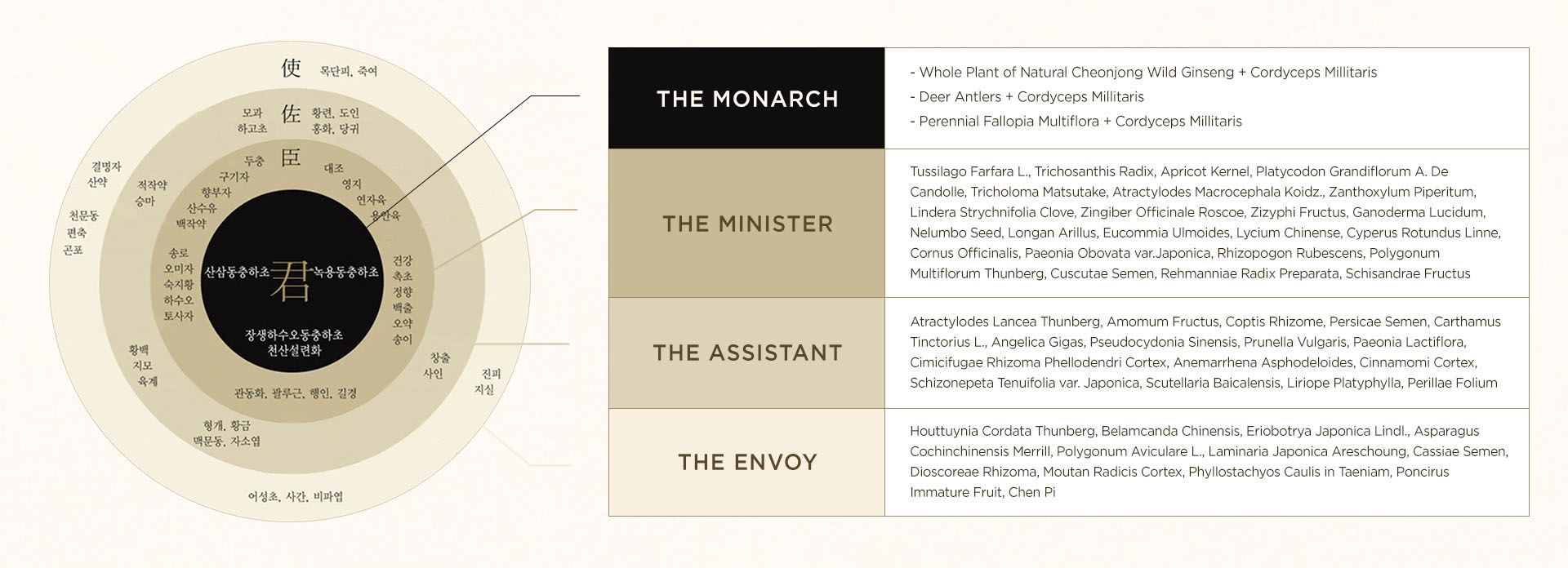

Below an example of the application of the Gunsinjwasa principle in the formula of a cosmetic product. In the picture the core formula for The History of Whoo’s Hwanyu line.

[click to enlarge]

Part 4: English Books on Traditional Korean Medicine

Seoul Selection, “Korean Medicine: A Holistic Way to Health and Healing” (2013)

Lee J., Lee C., “Introduction to Traditional Korean Medicine” (2007)

Sangwoo A., et al., “How to read Dounguibogam easily” (2008)

Notes

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. (2011). 한방화장품 표시・광고 가이드라인.

- Genie Park. (2004). [한방특집]웰빙열풍에 힘입어 부각.

- Rho H. (2011). 한방화장품개발 및 시장현황. NICE.

- The Kbeauty Science. (2019, January 14). 중국, 한국 화장품 포장에 ‘한방’ 표기 불허.

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. (2021). 화장품법.

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. (2021). 화장품법 시행령.

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. (2021). 화장품 표시기준 및 방법.

- Rho H. (2011). 한방화장품개발 및 시장현황. NICE.

- Han M. (2017). On the Scent of a Beautiful Life. Ebury Press.

- Genie Park. (2006). 태평양, ‘한방’ 집대성 추진.

- 정혜일. (2020) 한방 화장품에 대한 인식과 사용실태에 관한 연구. 학위논문(석사)– 성신여자대학교 뷰티융합대학원 : 뷰티융합학과 화장품학 전공.

- 파이낸셜투데이. (2019). ‘발상의 전환’ 한방화장품으로 中 젊은 층 유혹하는 신세계.

- Cometic Insight. (2021) LG생활건강, 2021 ‘광군제’ 역대 최대 매출액 ‘경신’.

- LG Household & Health Care. (2007). LG H&H Opens Whoo Oriental Medicine Skin Science Research Center, the First of its Kind in the Industry.

- Business Report. (2020). [M&A] LG생활건강, 자회사 ‘오비엠랩’ 흡수합병.

- Choi J., et al. (2015). The Determinants of Choosing Traditional Korean Medicine or Conventional Medicine: Findings from the Korea Health Panel.

- Pusan National University School of Korean Medicine. (2015). Korean Medicine: Current Status and

Future Prospects. - Science Direct. (2021). Integrative Medicine Research.

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. (2019). 한약(생약)제제 등의 품목허가·신고에 관한 규정.

- Jeong H. (2009) 인삼ㆍ산양삼ㆍ자연산 산삼의 ginsenoside 함량 분석 및 홍삼화 후 성분변화 비교. 상지대학교 학술정보원.

- Wang J., Sasse A., Sheridan H. (2019). Traditional Chinese Medicine: from aqueous extracts to therapeutic formulae. Plant Extracts. IntechOpen.

- Jia, W., Gao, W. Y., Yan, Y. Q., Wang, J., Xu, Z. H., Zheng, W. J., et al. (2004). The rediscovery of ancient Chinese herbal formulas. Phytother. Res.

- Kim, H., Ryu, J., Lee, J. et al. (2015). A systems approach to traditional oriental medicine. Nat Biotechnol

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. (2020). Study on the origin and description of herbal materials registered in the official compendium – Focus on multiple origins, such as other species of the same genus, allied plants or animals.

- NewsH. (2016). Korean Traditional Colors.

- World Health Organization. (2007). “WHO International Standard Terminologies on Traditional Medicine in the Western Pacific Region.”

Selected Sources and Suggestions for Further Reading

- Dongcheng L., Yu Q. (2012). Demystified Chinese Herbal Medicine. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Ganzhong, L. (2003). The Essentials of Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine. Foreign Languages Press.

- Genie Park. (2004, May 28). [한방특집]웰빙열풍에 힘입어 부각

- Han M. (2017). On the Scent of a Beautiful Life. Ebury Press.

- Lee B., at al. (2021). Regulation and status of herbal medicine clinical trials in Korea. Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine.

- Li X. (2017). Introductory Chapter: Therapies Based on Kidney Essence and Qi in Chinese Medicine. IntechOpen.

- Li, L. (1995). Practical Traditional Chinese Dermatology. Hong Kong: Hai feng Publishing Co.

- Ma S., Jia C., Guo J. (2019) The metaphor analysis of “monarch, minister, assistant and envoy” in TCM formula based on the concept of “a prescription being a state”. Journal of Beijing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. (2020). 기능성화장품 기준 및 시험방법.

- Park, Hansu & Lee, ByungWook & Lee, Boo-Kyun. (2014). A study on the comparative method of prescription using gunsinjwasa theory. Herbal Formula Science.

- Sangwoo A., et al. (2008). How to read Dounguibogam easily. Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine.

- Seoul Selection. (2013). Korean Medicine: A Holistic Way to Health and Healing. Seoul Selection.

- Sionneau, P., & Flaws, B. (1995). Pao Zhi: An Introduction to the Use of Processed Chinese Medicinals. Amsterdam University Press.

- Su, X., Yao, Z., Li, S., & Sun, H. (2016). Synergism of Chinese Herbal Medicine: Illustrated by Danshen Compound. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM.

- Wang J., Sasse A., Sheridan H. (2019). Traditional Chinese Medicine: from aqueous extracts to therapeutic formulae. Plant Extracts. IntechOpen.

- Wang L., Zhou G.-B., Liu P., et al. (2008). Dissection of mechanisms of Chinese medicinal formula Realgar-Indigo naturalis as an effective treatment for promyelocytic leukemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

- Wu X, Wang S, Lu J, Jing Y, Li M, Cao J, Bian B, Hu C. (2018). Seeing the unseen of Chinese herbal medicine processing (Paozhi): advances in new perspectives. Chin Med.

- Xuefeng S., Zhuoting Y., Shengting L., He S. (2016). Synergism of Chinese Herbal Medicine: Illustrated by Danshen Compound. Hindawi Publishing Corporation.

- Zhou X, Seto SW, Chang D, Kiat H, Razmovski-Naumovski V, Chan K and Bensoussan A (2016) Synergistic Effects of Chinese Herbal Medicine: A Comprehensive Review of Methodology and Current Research. Front. Pharmacol.

- 김남일 저. (2013). 한방화장품의 문화사. 도서출판 들녘.

Words, Visuals: © 2024 Odile Monod unless otherwise stated.

The reproduction of any content, either in whole or in part, for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited without obtaining the explicit written consent of the author.

Disclaimer: The list above may contain a combination of affiliate and non-affiliate links. If you make a purchase through one of our affiliate links, we will earn a small commission (paid by third party companies, not you). Commissions help fund the content production of the Monodist. For more information on our affiliate policy please refer to the About page. Some links may be missing because the item is not available outside of Korea at the moment.